A lire sur: http://www.technologyreview.com/communications/40233/?nlid=nlcomm&nld=2012-04-30

Siri may not be the smartest AI in the world, but it's the most socially adept.

Things Reviewed:Siri (beta release, running on iPhone 4)

START http://start.csail.mit.edu

The Man Who Lied

to His Laptop: What Machines Teach Us about Human Relationships Clifford Nass

Current, 2010

Me:

"Should I go to bed, Siri?"

Siri:

"I think you should sleep on it."

It's hard not to admire a smart-aleck reply like that. Siri—the

"intelligent personal assistant" built into Apple's iPhone 4S—often

displays this kind of attitude, especially when asked a question that

pokes fun at its artificial intelligence. But the answer is not some

snarky programmers' joke. It's a crucial part of why Siri works so well.

The popularity of Siri shows that a digital assistant needs more

than just intelligence to succeed; it also needs tact, charm, and

surprisingly, wit. Errors cause frustration and annoyance with any

computer interface. The risk is amplified dramatically with one that

poses as a conversational personal assistant, a fact that has undone

some socially stunted virtual assistants in the past. So for Siri, being

likable and occasionally kooky may be just as important as dazzling

with feats of machine intelligence.

Siri has its origins in a research project begun in 2003 and

funded by the U.S. military's Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency

(DARPA). The effort was led by SRI International, which in 2007 spun off

a company that released the original version of Siri as an iPhone app

in February 2010 (the technology

was named among

Technology Review's

10 Emerging Technologies in 2009). This earlier Siri could do fewer

things than the one that later came built into the iPhone 4S. It was

able to access a handful of online services for making restaurant

reservations, buying movie tickets, and booking taxis, but it was

error-prone and never made a big hit with users. Apple bought the

startup behind Siri for an undisclosed sum just two months after the app

made its debut.

The Siri that appeared a year and a half later works astonishingly

well. It listens to spoken commands (in English, French, German, and

Japanese) and responds with either an appropriate action or an answer

spoken in a calm, suitably robotic female voice. Ask Siri to wake you up

at 8:00 a.m. and it will set the phone's alarm clock accordingly. Tell

Siri to send a text message to a friend and it will dutifully take

dictation before firing off your missive. Say "Where can I find a

burrito, Siri?" and Siri will serve up a list of well-reviewed nearby

Mexican restaurants, found by querying the phone's location sensor and

performing a Web and map search. Siri also has countless facts and

figures at its fingertips, thanks to the online "answer engine" Wolfram

Alpha, which has access to many databases. Ask "What's the radius of

Jupiter?" and Siri will casually inform you that it's 42,982 miles.

Siri's charismatic quality is entirely lacking in other

natural-language interfaces. Several companies sell virtual customer

service agents capable of chatting with customers online in typed text.

One example is Eva, created by the Spanish company Indysis. Eva can chat

comfortably unless the conversation begins to stray from the areas it's

been trained to talk about. If it does, then Eva will rather rudely

attempt to push you back toward those topics.

Siri also has some closer competitors in the form of apps

available for iPhones and Android devices. Evi, made by True Knowledge;

Dragon Go, from the voice-recognition company Nuance; and Iris, made by

the Indian software company Dexetra, are all variations on the theme of

a voice-controlled personal assistant, and they can often match Siri's

ability to understand and carry out simple tasks, or to retrieve

information. But they are much less socially adept. When I asked Iris if

it thought I should go to sleep, "Perhaps you could use the rest" was

its flat, humorless response.

Impressive though Siri is, however, the AI involved is not all

that sophisticated. Boris Katz, a principal research scientist at MIT's

Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab, who's been building

machines that parse human language for decades, suspects that Siri

doesn't put much effort into analyzing what a person is asking. Instead

of figuring out how the words in a sentence work together to convey

meaning, he believes, Siri often just recognizes a few keywords and

matches them with a limited number of preprogrammed responses. "They

taught it a few things, and the system expects those things," he says.

"They're very clever about what people normally ask."

In contrast, conventional artificial-intelligence research has

strived to parse more complex meaning in conversations. In 1985, Katz

began building a system called START to answer questions by processing

sentence structure. That system answers typed questions by analyzing how

the words are arranged, to interpret the meaning of what's being asked.

This enables START to answer questions phrased in complex ways or with

some degree of ambiguity.

In 2006—a year before SRI spun off its startup—Katz and colleagues

demonstrated a software assistant based on START that could be accessed

by typing queries into a mobile phone. The concept is remarkably

similar to Siri, but this part of the START project never progressed any

further. It remained less important than Katz's pursuit of his real

objective—to create a machine that can better match the human ability to

use language.

To understand how difficult it is

to get communication right, you need look no further than the infamous

intelligent assistant Clippy, introduced by Microsoft in 1997.

START is just a tiny offshoot of the research into artificial

intelligence that began some 50 years earlier as an attempt to

understand the functioning of the human mind and to create something

analogous in machines. That effort has produced many truly remarkable

technologies, capable of performing computational tasks that are

impossibly complicated for humans. But artificial-intelligence research

has failed to re-create many aspects of human intellect, including

language and communication. As Katz explains, a simple conversation

between two people can tap into the full depth of a person's life

experiences, and this remains impossible to mimic in a machine. So even

as AI systems have become better at accessing, processing, and

presenting information, human communication has continued to elude them.

Despite being less capable than START at dealing with the

complexities of language, Siri shows that a machine can pull off just

enough tricks to fool users into feeling as if they're having something

approximately like a real conversation. To understand how difficult it

is to get even simple text-based communication right, you need look no

further than the infamous intelligent assistant introduced by Microsoft

back in 1997. This annoying virtual paper clip, called Clippy, would pop

up whenever a user created a document, offering assistance with a

message such as the infuriating line "It looks like you're writing a

letter. Would you like help?" Microsoft expected users to love Clippy.

Bill Gates thought fans would design Clippy T-shirts, mugs, and

websites. So the company was stunned, and confused, when users hated

Clippy, creating T-shirts, mugs, and websites dedicated to disparaging

it. The response was so bad that Microsoft killed Clippy off in 2007.

Before it did, Microsoft hired Stanford professor Clifford Nass,

an expert on human-computer interaction, to investigate why the program

had inspired so much unpleasantness. Nass, who is the author of

The Man Who Lied to His Laptop: What Machines Teach Us about Human Relationships, has

spent years studying similar phenomena, and his work suggests a fairly

simple cause: people instinctively apply the rules of human social

interactions to dealings with computers, cell phones, robots, in-car

navigation systems, and similar machines. Nass realized that Clippy

broke just about every norm of acceptable social behavior. It made the

same mistakes again and again, and constantly pestered users who wanted

to be left alone. "Clippy's problem was it said 'I'll do everything' and

then proceeded to disappoint," says Nass. Just as a person who repeats

the same answer again and again makes us feel insulted, Nass says, so

does a computer interface—even if we know full well we're dealing with a

machine.

Clippy showed that attempting more humanlike communication can

backfire spectacularly if the subtleties of social behavior aren't

understood and respected. Nass says Apple did everything possible to

make Siri likable. Siri doesn't impose itself on the user at all. The

application runs in the background on the iPhone, leaping to attention

only when the user holds down the "home" button or puts the phone to his

or her ear and starts speaking. It also avoids making the same mistake

twice, trying different answers when the user repeats a question. Even

the tone of Siri's voice was carefully chosen to be inoffensive, Nass

believes.

Apple also limited the tasks Siri can perform and the answers it

can give, most probably to avoid disappointment. If you ask Siri to post

something to Twitter, for example, it'll sheepishly admit that it

doesn't know how. But since the alternative could be accidentally

broadcasting garbled tweets, this strategy is understandable.

The accuracy of Siri's voice recognition also helps avoid

disappointment. The system does sometimes mishear words, often with

amusing results. "I'm sorry, Will, I don't understand 'I need pajamas'"

was a curious response to a question that had nothing to do with

pajamas. But mostly the voice system works remarkably well. It has no

problem with my English accent or with many complex words and phrases,

and this overall accuracy makes the odd mistake that much more

acceptable.

A key challenge for Apple was that soon after meeting Siri, a

person may experience a powerful urge to trip up this virtual

know-it-all: to ask it the meaning of life, whether it believes in God,

or whether it knows R2D2. Apple chose to handle this phenomenon in an

inventive way: by making sure Siri gets the joke and plays along. Thus

it has a clever answer for just about any curveball thrown at it and

even varies its responses, a trick that makes it seem eerily human at

times.

This banter also helps lessen the blow when Siri misunderstands

something or is stumped by a surprisingly simple question. Once, when I

asked who won the Super Bowl, it proudly converted one Korean won into

dollars for me. I knew this was just an algorithmic error in a distant

bank of computer servers, but I also felt the urge to interpret it as

Siri being zany.

Nass says the way Siri handles humor is inspired. Research has

revealed, he notes, that humor makes people seem smarter and more

likable. "Intermittent, innocent humor has been shown, for both people

and computers, to be effective," Nass says. "It's very positive, even

for the most boring, staid computer interface."

But Katz, as someone who has been striving for decades to give

machines the ability to use language, hopes eventually to see something

much more sophisticated than Siri emerge: a machine capable of holding

real conversations with people. Such machines could provide fundamental

insights into the nature of human intelligence, he says, and they might

provide a more natural way to teach machines how to be smarter.

That might continue to be the dream of AI researchers. For the

rest of us, though, the arrival of a virtual assistant that is actually

useful is just as fundamental a breakthrough. In Katz's office at MIT, I

showed him some of the amusing answers Siri comes up with when

provoked. He chuckled and remarked at the cleverness of the engineers

who designed Siri, but he also spoke as an AI researcher using meanings

and words that Siri would undoubtedly struggle with. "There's nothing

wrong with having gimmicks," he said, "but it would be nice if it could

actually analyze deeply what you said. The conversations with the user

will be that much richer."

Katz is right that a more revolutionary intelligent personal

assistant—one that's capable of performing many more complicated

tasks—will need more advanced AI. But this also underplays an important

innovation behind Siri. After testing the app a while longer, Katz

confessed that he admires entrepreneurs who know how to turn advances in

computer science into something that ordinary people will use every

day. "I wish I knew how people do that," he admits.

For the answer, perhaps he just needs to keep talking to Siri.

Will Knight is Technology Review

's online editor.

En

ce contexte tendu, toutes les économies sont bonnes à prendre. Surtout

si elles contribuent à réduire les temps de cycle et fiabiliser les

processus. Les flux d’informations dans les interactions entre les

entreprises sont un gisement insuffisamment exploité à cause d’aprioris

de coût, de complexité ou de maturité. Pourtant, leur dématérialisation

ouvre de réelles perspectives, à condition de penser autrement qu’en

termes de fichiers transmis par e-mail ou d’extranets.

En

ce contexte tendu, toutes les économies sont bonnes à prendre. Surtout

si elles contribuent à réduire les temps de cycle et fiabiliser les

processus. Les flux d’informations dans les interactions entre les

entreprises sont un gisement insuffisamment exploité à cause d’aprioris

de coût, de complexité ou de maturité. Pourtant, leur dématérialisation

ouvre de réelles perspectives, à condition de penser autrement qu’en

termes de fichiers transmis par e-mail ou d’extranets. La

fidélisation de la clientèle des banques est toujours problématique et

ce même si la situation s'est légèrement améliorée. L'indice CEI* (Customer Experience Index) de la neuvième édition du « World Retail Banking Report », publiée par Capgemini et l'Efma (European Financial Marketing Association),

révèle que 9 % des clients sont susceptibles de quitter leur

établissement financier au cours des six prochains mois et 40 % ne sont

pas sûrs de rester fidèles à leur banque à long terme. Au-delà d'une

nécessaire optimisation de l'expérience client, le rapport révèle

également que le potentiel des services bancaires mobiles n'a pas encore

été pleinement exploité.

La

fidélisation de la clientèle des banques est toujours problématique et

ce même si la situation s'est légèrement améliorée. L'indice CEI* (Customer Experience Index) de la neuvième édition du « World Retail Banking Report », publiée par Capgemini et l'Efma (European Financial Marketing Association),

révèle que 9 % des clients sont susceptibles de quitter leur

établissement financier au cours des six prochains mois et 40 % ne sont

pas sûrs de rester fidèles à leur banque à long terme. Au-delà d'une

nécessaire optimisation de l'expérience client, le rapport révèle

également que le potentiel des services bancaires mobiles n'a pas encore

été pleinement exploité.

Google annonce le lancement officiel de Google Drive, son service de stockage en ligne grand public. " Ces derniers temps, vous avez dû entendre des rumeurs sur Google Drive, un peu comme la chimère du monstre du Loch Ness, explique Sundar Pichai, SVP, Chrome & Apps.

Aujourd’hui, l’une de ces deux rumeurs est devenue réalité. Nous

lançons aujourd’hui Google Drive, votre espace pour créer, partager,

collaborer et conserver tous vos documents. Travailler avec un ami sur

un projet de recherche, préparer votre mariage avec votre moitié, suivre

l'état de vos comptes avec vos colocataires : tout cela est possible

dans Drive. Vous pouvez télécharger et accéder à tous vos fichiers, des

vidéos aux PDF, en passant par vos photos et Google Documents ".

Google annonce le lancement officiel de Google Drive, son service de stockage en ligne grand public. " Ces derniers temps, vous avez dû entendre des rumeurs sur Google Drive, un peu comme la chimère du monstre du Loch Ness, explique Sundar Pichai, SVP, Chrome & Apps.

Aujourd’hui, l’une de ces deux rumeurs est devenue réalité. Nous

lançons aujourd’hui Google Drive, votre espace pour créer, partager,

collaborer et conserver tous vos documents. Travailler avec un ami sur

un projet de recherche, préparer votre mariage avec votre moitié, suivre

l'état de vos comptes avec vos colocataires : tout cela est possible

dans Drive. Vous pouvez télécharger et accéder à tous vos fichiers, des

vidéos aux PDF, en passant par vos photos et Google Documents ".

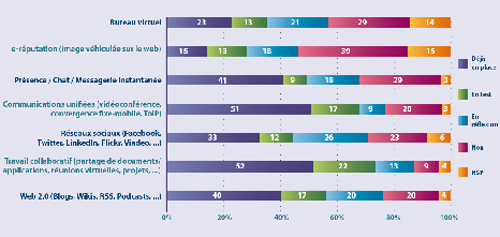

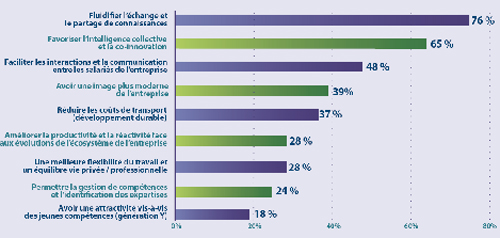

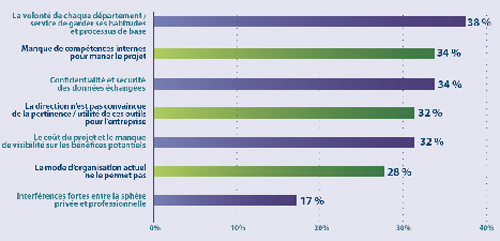

Comment

sont perçus et utilisés les outils 2.0 en entreprise ? En veille sur

les tendances et les besoins émergeants des entreprises,

Aastra, spécialiste des communications d’entreprise, publie les

résultats d'une étude réalisée en partenariat avec NotezIT. Cette

enquête a été menée auprès des cadres dirigeants d’un large panel

d’entreprises françaises de tous secteurs et toutes tailles confondus.

Son objectif : évaluer comment les entreprises et leurs collaborateurs

se situent face à ces nouveaux modes de communications (impact sur la

compétitivité, sur l’équilibre vie personnelle/vie professionnelle,

freins éventuels rencontrés, etc.).

Comment

sont perçus et utilisés les outils 2.0 en entreprise ? En veille sur

les tendances et les besoins émergeants des entreprises,

Aastra, spécialiste des communications d’entreprise, publie les

résultats d'une étude réalisée en partenariat avec NotezIT. Cette

enquête a été menée auprès des cadres dirigeants d’un large panel

d’entreprises françaises de tous secteurs et toutes tailles confondus.

Son objectif : évaluer comment les entreprises et leurs collaborateurs

se situent face à ces nouveaux modes de communications (impact sur la

compétitivité, sur l’équilibre vie personnelle/vie professionnelle,

freins éventuels rencontrés, etc.).

La

vocation structurante des stratégies informatiques ne conduit-elle pas à

l'immobilisme, au manque de créativité et à l'absence de réactivité?

Ou, "peut-on donner de l'agilité à l'alignement stratégique, qui a pour

vocation à structurer lourdement une politique informatique ?". Au-delà

des solutions classiques qui touchent aux moyens et aux hommes, des

nouvelles offres logicielles apparaissent désormais sur le marché, et il

est certain que c'est à partir de ces solutions, de type Smart

Computing, que les directeurs des services Informatiques se

transformeront plus encore plus en directeur des systèmes d'information.

La

vocation structurante des stratégies informatiques ne conduit-elle pas à

l'immobilisme, au manque de créativité et à l'absence de réactivité?

Ou, "peut-on donner de l'agilité à l'alignement stratégique, qui a pour

vocation à structurer lourdement une politique informatique ?". Au-delà

des solutions classiques qui touchent aux moyens et aux hommes, des

nouvelles offres logicielles apparaissent désormais sur le marché, et il

est certain que c'est à partir de ces solutions, de type Smart

Computing, que les directeurs des services Informatiques se

transformeront plus encore plus en directeur des systèmes d'information. Certaines

tendances du cloud vont s'accélérer, changer ou atteindre un tournant

au cours des trois prochaines années. Il est essentiel de surveiller

continuellement les tendances du cloud computing et de mettre

régulièrement à jour la stratégie cloud de l'entreprise afin d'éviter de

coûteuses erreurs ou de manquer les opportunités du marché.

Certaines

tendances du cloud vont s'accélérer, changer ou atteindre un tournant

au cours des trois prochaines années. Il est essentiel de surveiller

continuellement les tendances du cloud computing et de mettre

régulièrement à jour la stratégie cloud de l'entreprise afin d'éviter de

coûteuses erreurs ou de manquer les opportunités du marché.